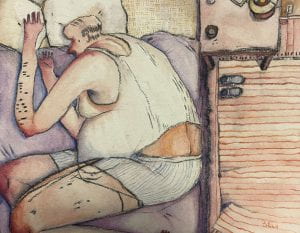

Bela Siptak, Henry’s Night. Guache and charcoal, 2024.

Larry had spent the last five minutes searching his apartment for nail clippers–partly because he’d been taking his LEGO Imperial Star Destroyer apart piece by piece over and the course of the week and the Empire struck back on his fingernails, but mostly because it was five minutes he did not have to spend trying to get dressed. Five minutes not staring at himself in the mirror.

He’d torn through all of his closet’s storage and tried every combination of baggy pants and polo shirt before finally being forced to come to terms with the fact that his wardrobe was not the problem.

In his youth, Larry had served a short stint as the smartest kid in class. It was a status he’d be paying interest on for the rest of his life—because it’d turned out to be a very expensive, valedictorian-fitted suit that was never actually his—but it afforded him just enough lasting brilliance to be begrudgingly cognizant of his own balding head.

He developed a liking towards beanies, baseball caps and various similar forms of headwear, though they were always inevitably drawn into orbit of the celestial body that was his bald spot. His sister informed him they all looked ugly on him and were not subtle, which he already knew but hated that other people might, so he recently donated most of them.

In summary, yes, he’d been aware of it, in the unfortunate way Larry was often aware of things he would rather not be. For example, that his mother could die in a car accident and he probably wouldn’t know until their next bi-weekly phone call, or the ever-looming threat of rent payment.

There was a certain psychological distance he needed to maintain with these stressors, lest they mangle the magnetic field of his mental equilibrium. He worried about them, like he did most things, just with a serving size of abstraction and a healthy dose of intangibility, like watching something through a car’s side-view mirror. With it, came the occasional downside of objects in the mirror encroaching very suddenly and causing catastrophic accidents.

The most recent of these instances involved the metaphorical “side-view mirror” being torn clean off by the ambulance that took him to the hospital when he collapsed at work three weeks ago, and the “catastrophic accident” was the bill he received for it when his insurance neglected to keep it from crashing headlong into his upcoming rent payment.

Larry came equipped with an otherwise useless sociology degree, and figured that between his niece’s birthday gift and his rent payment, Maslow would want him to opt for the latter. Larry, whose pyramid was more the shape of a plateau—crumbly around the esteem bits with self-actualization comfortably out of reach—decided he was going to have them both anyways.

And so went his Star Destroyer, plucked apart and unrecognizable without the picture on the box. His fingernails were, unfortunately, lost in the disaster.

And his nail clippers were nowhere to be found throughout the vast expanse of his tiny apartment. The Empire seemed to be after the rest of his nails too, with how often he stubbed his toe on the box while flitting around.

He marched his retreat back to his dastardly mirror, recalling the last time his sister visited, and how he’d let her use them.

They must’ve been lost to the black hole of her infinite pockets, gravitational giants compounded by a childhood of ransacking 7-Elevens for more money in sweets than their older brother brought to spend on his cigarettes in the first place. Larry could hardly be upset about the vestiges of her kleptomaniac tendencies, not after the windfall it’d graced him with in adolescence.

He would be forced to attend his niece’s birthday party with the price of his gift worn on his fingertips like battle scars, and hope he didn’t forget to get his nail clippers back before he left their house.

It was in the failure of his nail-oriented side quest that he was forced to refocus on his primary concern: that of the mirror, his hair, and the lack of it.

The remains of the “outfits” he’d tried on were strewn across the floor in ways that made it comically obvious that all of them looked about the same, and that no shade of green flannel would ever dull the shine of his bald spot.

He would like to call it a burgeoning patch, but more correctly it would be burgeoned, having swelled and spread beneath the hat he wore with his work uniform and gone ignored in a bid for denial outside of that.

Just a few months ago he even had the good humor to joke about it. He told Sonia—whose favorite place to be was tall and wanted to go to space to meet Harrison Ford one day but for now would settle for riding around on her uncle’s shoulders and petting his head like it was a control panel—that she was stealing his hair away every time she touched his head.

He’d had the lightheartedness to panic earnestly when reassuring her that she was in no way “a hair-stealing-goblin,” and to laugh when his sister declared that every child ought to have something they wildly misunderstood about the world (that babies came from UFO’s) for them to look back on fondly (or for their sisters to look back on hysterically and never stop bringing up).

But now he has neither. And he wonders if he’ll be able to keep up the act. If he can bear to arrive at his niece’s party, sans plainly obvious beanie (because that would be worse), and have all the rest of his family really see his age, to watch it dawn on their faces for probably the first time.

He’s known for a while, of course. But most of them still see him as a kid who’s just starting off. His apartment, merely cost-efficient. His job, only temporary. A kid who’ll get off his butt any day now, start his own business, become a doctor, and go to space.

Larry used to love space. He still did. It was a fondness abstracted by growing pains, body odor and male pattern baldness, but was probably still there, somewhere. In the shape of LEGO Star Destroyers taking up more space than it could afford in his apartment, in the way he became Sonia’s favorite uncle by being the only relative who cared much about planets, and could keep up with an impassioned discussion about how Pluto definitely was one.

Oh it’d been a much more concrete fascination, when he was the smart kid. When he had so much potential, when compared to his two siblings he didn’t have even an hour of summer classes, detention, or alternate school to his name.

When he was the kid in his borrowed little valedictorian-shaped suit, dressed for the vague notion of a job he would never have, who won spelling bees and math tests and could probably make it to space if he tried real, real hard.

He’d grown out of being that kid. His aspirations settled to more reasonable skylines. For Larry, the stars lost a lot of their sparkle when he stopped really believing he could reach them. And so he shed the fervent fascination while it was still a pleasant memory, understanding even then that he didn’t have the strength to bear a dream that big. He gave it up before it could start crushing him.

Larry likes his hair. And as he runs his stinging fingers through the sparse and sparser weeds of it he wonders when he’ll have to say he liked his hair, too.

There are two types of clippers in his apartment, see. And as he stares at the other, sitting on the bathroom sink, he wonders if it might be better if he gets to say it before anyone else does. If he can leave it as a pleasant memory, rather than let the crowd gawk as he claws on to its vestiges. His misshapen nails meet hair clippers with the softest tap.

See, there is very little Larry is better at than giving up.

He shrunk out of his little borrowed suit as soon as the real owners showed up to take their places. His type A personality slipped to B-minuses, and nobody really bothered to keep track, after that.

Larry’s greatest successes now were his building’s loudest tenants moving out, Sonia calling him her favorite uncle for the seventh time, and his brother venmo-ing him $20 when his most listened song was one from their new album. The idea that all of that is a failure of some kind really only troubles him when he drinks too much of the beer in the child-locked part of his sister’s fridge, or when his mother is within a 10-mile radius.

He is told the day he switched that suit for a band shirt and then every day after that—never in exact words but always, always audible—that his greatest mistake was ‘quitting while he was ahead’. That their very human sadness at the thought of him losing out on something great out of cowardice or complacency. It’s spoken in the sigh on his mother’s breath when he tells her he doesn’t intend on taking AP Statistics next year, and the scowl on his older brother’s face the day he quit their band.

He wants to explain, sometimes. Put to words the starkly alien sadness in knowing that you wouldn’t have made it any farther anyway. In throwing in the towel rather than watching it slip off your shoulders. In knowing that, for you, this will be the end of the line. That your only consolation is getting off at your last stop with the pretense of choice. Choosing whether you bank to the sidelines with a smile pasted on your face or collapse mid-race.

He never does explain. His sadness burns from a different core than theirs. Echoes from an entirely different planetary system. It feels like a waste, laying the very expanse of his soul out on the table to be picked and prodded. He’d be dissected and re-catalogued. So simply, too. Shelved away with all the other disappointments they talk about at family reunions. Some people would never believe in aliens. He never explains.

Larry, the alien, extraterrestrially good at burning the candle on only one end, at sparing the wick of its last dregs. Larry, the master, not of quitting while he’s ahead, but of bearing the race for only as long as he can stand it. Larry, the collector of pleasant memories.

And so the hair goes.

Maybe he’s a coward. Maybe he’s a disappointment.

The strands fall all the same.

When he arrives at the party, Sonia stares at him for several toddler heartbeats (equivalent to one business blink) and compares him to the alien emoji.

A little later, an asteroid.

A planet.

The Death Star.

She develops a long standing habit of always touching peoples heads.